It all began with the mess of an unplanned urbanization, letting things turn out as they came along, and “let whoever comes behind fix it.”

The irregularity with which the Havana township of San Cristóbal was formed is reflected in the Cabildo (town council), where an alderman screamed out that “the streets be named, so that it is understood where the houses are to be built.”

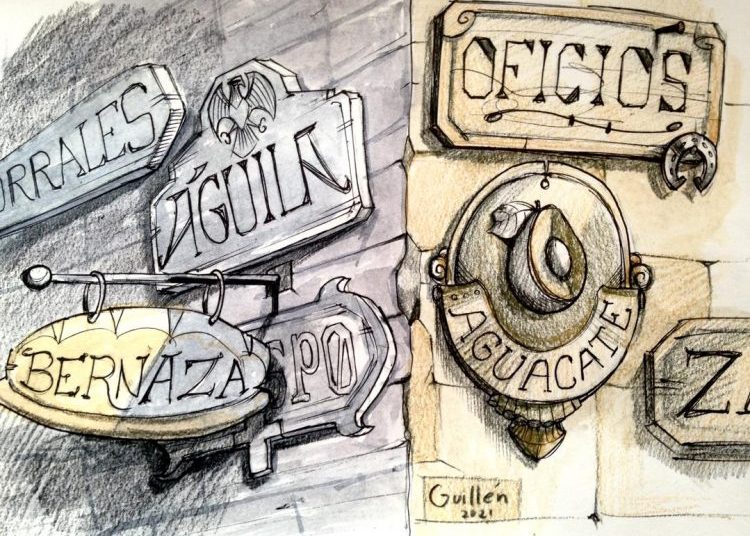

Following a method not exempt of daily poetry, the people started nominating the streets on the basis of circumstantiality. One was identified by the large number of artisans who practiced their trades (OFICIO) there; another, for a bishop’s (OBISPO) morning walks; a third for the lamp (LAMPARILLA) that a devotee lit before a religious image.

The eagle (AGUILA) painted on a tavern sign, a lush avocado (AGUACATE) tree, a still (ALAMBIQUE) or duct (ZANJA), the first aqueduct in the Americas, could also be the basis for the popular denomination.

Then there’s the pillory (PICOTA) where the prisoners were flogged, the lonely and helplessness of a place that seemed on purpose for the sorrowful (ANIMAS), and the stones (EMPEDRADO) with which a street was experimentally covered in which a large volume of water flowed in times of rain, a place where novelist Alejo Carpentier begins the action of El siglo de las Luces.

Nor were cattle corrals (CORRALES) missing, a large lantern in the shape of a star (ESTRELLA) or the perseverance (PERSEVERANCIA) it took for the construction of a street.

Leave a Reply